Cranes of the World

Cranes make up the family, Gruidae. They are large, long-legged and long-necked birds in the group Gruiformes. There are fifteen species of crane in four genera. Unlike the similar-looking but unrelated herons, cranes fly with necks outstretched, not pulled back. Cranes live on all continents except Antarctica and South America.

They are opportunistic feeders that change their diet according to the season and their own nutrient requirements. They eat a range of items from suitably sized small rodents, fish, amphibians, and insects to grain, berries, and plants.

Cranes construct platform nests in shallow water, and typically lay two eggs at a time. Both parents help to rear the young, which remain with them until the next breeding season.

Some species and populations of cranes migrate over long distances; others do not migrate at all. Cranes are solitary during the breeding season, occurring in pairs, but during the non-breeding season they are gregarious, forming large flocks where their numbers are sufficient.

Most species of cranes have been affected by human activities and most are classified as threatened, to critically endangered. The plight of the Whooping Cranes of North America inspired some of the first US legislation to protect endangered species.

Cranes are large to very large birds, including the world's tallest flying bird. They range in size from the Demoiselle Crane, which measures 90 cm (35 in) in length, to the Sarus Crane, which can be up to 176 cm (69 in), although the heaviest is the Red-crowned Crane, which can weigh 12 kg (26 lb) prior to migrating. They are long-legged and long-necked birds with streamlined bodies and large rounded wings. The males and females do not vary in external appearance, but on average males tend to be slightly larger than females.

The plumage of the cranes varies by habitat. Species inhabiting vast open wetlands tend to have more white in the plumage than do species that inhabit smaller wetlands or forested habitats, which tend to be more grey. These white species are also generally larger. The smaller size and colour of the forest species is thought to help them maintain a less conspicuous profile while nesting; two of these species (the common and sandhill cranes) also daub their feathers with mud to further hide while nesting.

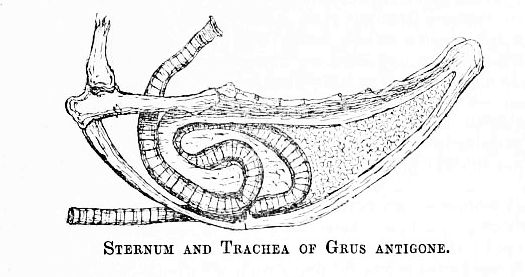

The long coiled trachea that produces the trumpeting calls of cranes.

Most species of crane have some areas of bare skin on the face; the only two exceptions are the Blue and Demoiselle Cranes. This skin is used in communication with other cranes, and can be expanded by contracting and relaxing muscles, and change the intensity of colour. Feathers on the head can be moved and erected in the Blue, Wattled and Demoiselle Cranes for signalling as well.

Also important to communication is the position and length of the trachea. In the two species of Crowned Cranes the trachea is shorter and only slightly impressed upon the bone of the sternum, whereas the trachea of the other species is longer and penetrates the sternum. In some species the entire sternum is fused to the bony plates of the trachea, and this helps amplify the crane's calls, allowing them to carry for several kilometres.

Distribution and Habitats

The cranes have a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring across most of the world continents. They are absent from Antarctica and, mysteriously, South America. East Asia is the centre of crane diversity, with eight species, followed by Africa, which holds five resident species and wintering populations of a sixth. Australia, Europe and North America have two species. Of the four genera of crane, two, Balearica(two species) and Bugeranus (one species) are entirely restricted to Africa, and the third Anthropoides has one entirely African species and one species that is found in Africa, Asia and Europe. The remaining genus, Grus, contains the most species and is the most widespread genus, although only a single species occurs in Africa as a wintering migrant.

Most species of crane are dependent on wetlands and require large areas of open space. Most species of crane nest in shallow wetlands. Some species nest in wetlands but move their chicks up onto grasslands to feed (while returning to wetlands at night), whereas others remain in wetlands for the entirety of the breeding season. Even the two species of Anthropoides crane, which may nest and feed in grasslands (or even arid grasslands or deserts) require weedlands for roosting in during the night. The only two species that do not always roost in wetlands are the two African crowned-cranes (Balearica), which are the only cranes to roost in trees.

Some crane species are sedentary, remaining in the same area throughout the year, others are highly migratory, travelling thousands of kilometres each year from their breeding sites. A few species have both migratory and sedentary populations.

Ecology and Behaviour

Many species of cranes gather in large groups during migration and on their wintering grounds

Cranes are diurnal birds that vary in their sociability by season. During the breeding season, they are territorial and usually remain on their territory all the time, whilst out of the breeding season they tend to be gregarious, forming large flocks to roost, socialise, and, in some species feed.

Species that feed predominately on vegetable matter in the non-breeding season feed in flocks. Whereas those that feed on animals will usually feed in family groups, joining flocks only during resting periods, or in preparation for travel during migration. Large aggregations of cranes are important for safety when resting and also as places for young single birds to meet others.

Calls and Communication

Cranes are highly vocal and have a large vocabulary of specialized calls. The vocabulary begins soon after hatching with low, purring contact calls for maintaining contact with their parents, as well as food begging calls. Other calls used as chicks include alarm calls and “flight intention” calls, both of which are maintained into adulthood. The cranes’ duet calls are most impressive. They can be used for individual recognition.

Feeding

The cranes as a family consume a wide range of food types, including both animal and plant material. When feeding on dry land, they consume seeds, leaves, nuts and acorns, berries, fruit, insects, worms, snails, small reptiles, mammals, and birds. In wetlands, food sources include roots, rhizomes, tubers and other parts of emergent plants, molluscs, small fish, and amphibians. The exact composition of the diet varies by location, season, and availability. Within the wide range of items consumed there are some patterns; the shorter-billed species of cranes usually feed in drier uplands while the longer-billed species feed in wetlands.

Cranes employ different foraging techniques for different food types. A crane digging for tubers and rhizomes may remain in place for some time digging and then expanding a hole to find them. In contrast to the stationary wait and watch hunting techniques employed by many herons, cranes forage for insects and animal prey by slowly moving forwards with their heads lowered and probing with their bills.

Where more than one species of crane exists in a locality, each species will adopt separate niches in order to minimize competition and niche overlap. At one important lake in Jiangxi Province in China, the Siberian Cranes feed on the mudflats and in shallow water, the White-naped Cranes on the wetland borders, the Hooded Cranes on sedge meadows and the last two species also feed on the agricultural fields along with the Common Cranes.

One of the points of human conflict with cranes and a reason for the loss of cranes through poisoning and hunting, is crop damage caused by cranes. This is particularly true of young crops, as the seedlings emerge, they are attractive to many crane species.

Breeding

Cranes are perennially monogamous breeders, establishing long-term pair bonds that may last the lifetime of the birds. Pair bonds begin to form in the second or third years of life, but it may be several years before the first successful breeding season is achieved. Initial breeding attempts often fail, and in many cases newer pair bonds will dissolve after unsuccessful breeding attempts. Pairs that are repeatedly successful at breeding will remain together. In a study of Sandhill Cranes in Florida, seven out of the 22 pairs studied remained together for an 11-year period. Of the pairs that separated, death of one of the pair was the primary cause (53%), whilst 18% parted after unsuccessful breeding attempts, reasons for the parting of the remaining 29% of pairs is unknown. Similar results has been found by acoustic monitoring (sonography / frequency analysis of duet and guard calls) in 3 breeding areas of Common Cranes in Germany over 10 years.

Cranes are territorial and generally seasonal breeders. Seasonality varies both between and within species, dependent on local conditions. Migratory species begin breeding upon reaching their summer breeding grounds, between April and June. The breeding season of tropical species, however, is usually timed to coincide with the wet or monsoon seasons. Territory sizes also vary depending on location. Tropical species can maintain very small territories, for example, Sarus Cranes in India can breed on territories as small as one hectare where the area is of sufficient quality and disturbance by humans is minimized.

In contrast Red-Crowned crane territories may require 500 hectares, and pairs may defend even larger territories than that, up to several thousand hectares. Territory defense is usually performed by the male.Because of this females are much less likely to retain the territory than males in the event of the death of a partner.

Crane Taxonomy and Systemics

There are 15 living species of cranes in four genera.

SUBFAMILY Balearicinae Crowned Cranes

Genus Balearica: two species

Black Crowned Crane Balearica Pavonina

The Black Crowned Crane occurs in dry savannah in Africa south of the Sahara, although in nests in somewhat wetter habitats. There are two subspecies: B. p. pavonina in the west and the more numerous B. p. ceciliae in east Africa.This species and the closely related Grey Crowned Crane, B. regulorum, which prefers wetter habitats for foraging, are the only cranes that can nest in trees. This habit, amongst other things, is a reason the relatively small Balearica cranes are believed to closely resemble the ancestral members of the Gruidae. It is about 1 m long, has a 1.87 m wingspan and weighs about 3.6 kg.

Like all cranes, the Black Crowned Crane eats insects, reptiles, and small mammals. It is endangered, especially in the west, by habitat loss and degradation.

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica Regulorum

One of our indigenous species. Read more about Grey Crowned Cranes on their dedicated page.

SUBFAMILY GRUINAE Typical Cranes

Genus Leucogeranus: one species

Siberian Crane Leucogeranus leucogeranus

The Siberian Crane (Leucogeranus leucogeranus), also known as the Siberian White Crane or the Snow Crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae.

They are distinctive among cranes in that adults are predominantly snowy white, with only their primary feathers being black, which makes them only visible in flight.

There are two breeding populations, one in the Arctic tundra of western and eastern Russia. The eastern populations migrate during winter to China while the western population winters in Iran and formerly, in India and Nepal. Among the cranes, they make the longest distance migrations.

The populations, particularly those in the western range, have declined drastically in the 20th century due to hunting along their migration routes and habitat degradation. The world population was estimated to be about 3,200 birds, in 2010. Mostly belonging to the eastern population with about 95% of them wintering in the Poyang Lake basin in China, a habitat that may be altered by the Three Gorges Dam. In western Siberia there are only around ten of these cranes in the wild.

Genus Antigone: four species

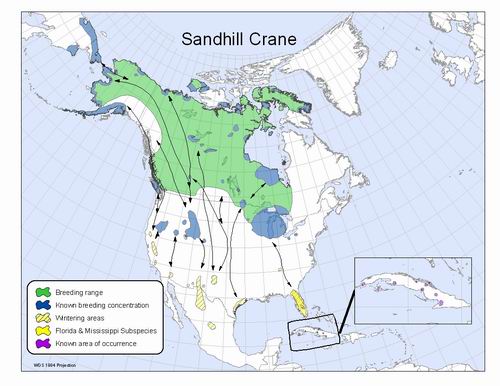

Sandhill Crane Antigone Canadensis

The Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis) is a species of large cranes of North America and extreme north eastern Siberia. The common name refers to the birds prefered habitat in the area of the Platte River, on the edge of Nebraska’s Sandhills on the North American Plains. This is the most important stopover area for the nominotypical subspecies, the Lesser Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis canadensis), with up to 450,000 of these birds migrating through the area annually.

White-naped Crane Antigone Vipio

The White-naped Crane (Antigone vipio) is a large bird, 112–125 cm long, approximately 130 cm tall and weighing about 5.6 kg. They have pinkish legs, grey and white striped neck, and a red face patch.

The White-naped Crane breeds in north-eastern Mongolia, north-eastern China, and adjacent areas of south-eastern Russia where a programme at Khingan Nature Reserve raises crane eggs provided from U.S. zoos to bolster the species. Different groups of the birds migrate to winter near the Yangtze River, the DMZ in Korea and on Kyūshū in Japan. They also reach Kazakhstan and Taiwan. Only about 4,900 and 5,400 individuals remain in the wild.

Its diet consists mainly of insects, seeds, roots, plants and small animals.

Due to ongoing habitat loss and overhunting in some areas, the White-naped Crane is deemed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is listed on Appendix I and II of CITES.

Sarus Crane Antigone Antigone

The Sarus Crane (Antigone antigone) is a large non-migratory crane found in parts of the Indian subcontinent, South-East Asia and Australia. The tallest of all flying birds, standing at a height of up to 1.8 m, they are a conspicuous and iconic species of open wetlands.

The Sarus Crane is easily distinguished from other cranes in the region by the overall grey colour and the contrasting red head and upper neck. They forage on marshes and shallow wetlands for roots, tubers, insects, crustaceans and small vertebrate prey.

Like other cranes, they form long-lasting pair-bonds and maintain territories within which they perform territorial and courtship displays that include loud trumpeting, leaps and dance-like movements. In India they are considered symbols of marital fidelity, believed to mate for life and pine the loss of their mates even to the point of starving to death. The main breeding season is during the rainy season, when the pair builds an enormous nest “island”, a circular platform of reeds and grasses nearly two metres in diameter and high enough to stay above the shallow water surrounding it.

Sarus Crane numbers have declined greatly in the last century and it has been estimated that the current population is a tenth or less (perhaps 2.5%) of the numbers that existed in the 1850s. The stronghold of the species is in India, where it is traditionally revered and lives in agricultural lands in close proximity to humans. Elsewhere, the species has been extirpated in many parts of its former range.

Brolga Antigone Rubicunda

The Brolga (Antigone rubicunda), formerly known as the Native Companion, . It has also been given the name Australian Crane, a term coined in 1865 by well-known ornithological artist John Gould in his Birds of Australia.

The Brolga is a common, gregarious wetland bird species of tropical and south-eastern Australia and New Guinea. It is a tall, upright bird with a small head, long beak, slender neck and long legs. The plumage is mainly grey, with black wing tips, and it has an orange-red band of colour on its head. It is well known for its intricate mating dance. The nest is built of sticks on an island in marshland and usually two eggs are laid. Incubation takes 32 days and the newly hatched young are precocial. The adult diet is mostly plant matter, but invertebrates and small vertebrates are also eaten.

Although the bird is not considered endangered over the majority of its range, populations are showing some decline, especially in southern Australia, and local action plans are being undertaken in some areas. It is the official bird emblem of the state of Queensland.

Genus Grus: eight species

Common or Eurasian Crane Grus Grus

The Common Crane (Grus grus), also known as the Eurasian Crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. The scientific name is from the Latin; grus, “crane”.

A medium-sized species, it is the only crane commonly found in Europe besides the Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo). Along with the Sandhill (Grus canadensis), the Demoiselle Crane and the Brolga (Grus rubicunda), it is one of only four crane species not currently classified as threatened with extinction or conservation dependent at the species level.

Whooping Crane Grus Americana

The Whooping Crane (Grus americana), the tallest North American bird, is named for its whooping call.

Along with the Sandhill Crane, it is one of only two crane species found in North America. The Whooping Crane’s lifespan is estimated to be 22 to 24 years in the wild. After being pushed to the brink of extinction by unregulated hunting and loss of habitat to just 21 wild and two captive whooping cranes by 1941, conservation efforts have led to a limited recovery. As of February 2015, the total population was 603 including 161 captive birds.

Hooded Crane Grus Monacha

The Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) is a small, dark crane. It has a grey body. The top of the neck and head is white, except for a patch of bare red skin above the eye. It is one of the smallest cranes, but is still a fairly large bird, at 1 m long, 3.7 kg and a wingspan of 1.87 m.

The Hooded Crane breeds in south-central and south-eastern Siberia. Breeding is also suspected to occur in Mongolia. Over 80% of its population winters at Izumi, southern Japan. There are also wintering grounds in South Korea and China. Approximately 100 hooded cranes winter in Chongming Dongtan, Shanghai every year. Dongtan Nature Reserve is the largest natural wintering site in the world. In December 2011, a hooded crane was seen overwintering at the Hiwassee Refuge in south-eastern Tennessee, well outside its normal range. In February 2012, one was seen at Goose Pond in southern Indiana, and is suspected to be the same bird, which may have migrated to North America by following sandhill cranes.

The estimated population of the species is 11,600 individuals. The major threats to its survival are wetland loss and degradation in its wintering grounds in China and South Korea as a result of reclamation for development and dam building. Conservation activities have been taken since 2008. Local universities, NGOs and communities are working together for a better and safer wintering location.

The Hooded Crane is evaluated as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is listed on Appendix I and II of CITES. A society, Grus monacha International Aid , has been formed to find ways to protect the species.

Black-necked Crane Grus Nigricollis

The Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) is a medium-sized Asian crane that breeds on the Tibetan Plateau and remote parts of India and Bhutan. It is 139 cm long with a 235 cm wingspan, and weighs 5.5 kg. It is whitish-gray, with a black head, red crown patch, black upper neck and legs, and white patch to the rear of the eye. It has black primaries and secondaries. Both sexes are similar. Some populations are known to make seasonal movements. It is revered in Buddhist traditions and culturally protected across much of its range. A festival in Bhutan celebrates the bird while the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir considers it to be the state bird.

Red-crowned Crane Grus Japonensis

The Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis), also called the Japanese Crane or Manchurian Crane, is a large East Asian crane 158 cm, tall, weighing 7.5 kg. The total population is only between 1,700 – 2,000 birds and declining IUCN: EN; ESA: E; Cites Appendix I; CMS I, II

Red-crowned Cranes are the only crane species that have white primary feathers. Adult forehead and crown are covered with bare red skin, and a large white band extends from behind the eyes and meets sharply with the black lower neck. The majority of the body is pure white with the exception of black secondary and tertiary feathers. Eyes are black and legs are slatey to grayish black. Males and females are virtually indistinguishable, although males tend to be slightly larger in size.

Juveniles are a combination of white, partly tawny, cinnamon brown, and/or grayish plumage. The neck collar is grayish to coffee brown, the secondaries are dull black and brown, and the crown and forehead are covered with gray and tawny feathers. The legs and bill are similar to those of adults, but lighter in color. The primaries are white, tipped with black, as are the upper primary coverts. At two years of age the primaries are replaced with all white feathers.

In some parts of its range, it is known as a symbol of luck, longevity and fidelity.

Blue Crane Anthropoides Paradisea

The national bird of South Africa and an indigenous species, please fin more information on the dedicated page for this species.

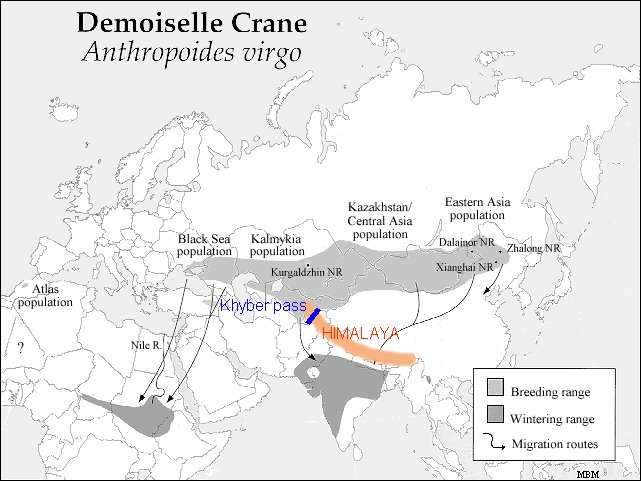

Demoiselle Crane Grus virgo

The Demoiselle Crane is a species of crane found in central Eurasia, ranging from the Black Sea to Mongolia and North Eastern China. There is also a small breeding population in Turkey. These cranes are migratory birds. Birds from western Eurasia will spend the winter in Africa, whilst the birds from Asia, Mongolia and China will spend the winter in the Indian subcontinent. The bird is symbolically significant in the culture of North India, where it is known as the koonj.

Wattled Crane Grus Carunculata

An indigenous species of South Africa, please find more information on the dedicated page for this species.