Blue Cranes

Summary

BLUE CRANES Anthropoides paradiseus

Conservation Status: Red Data Book of Birds of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland: Vulnerable. Cites Appendix II; CMS II

Identification: Large birds 1.0 - 1.2 m, adults +/- 5 kg (although they are one of the smaller crane species), plain blue-grey in overall colour with very long slate-grey tertials (resembling long tail streamers). Long black legs and feet. Brown to pink bill.

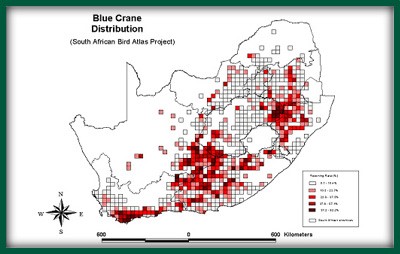

Distribution: Endemic to Southern Africa - Natural grassland, grassy Karoo, agriculturally transformed Renosterveld

Population: 20,000 to 21,000 in South Africa (Less than 50 elsewhere)

Main threats: Habitat loss, poisonings, powerline and wind turbine collisions.

Conservation: Landowner engagement in conservation, responsible use of agri-chemicals, co-operation with power generation and distribution authorities.

Identification

- Large elegant birds 1.0 – 1.2 m, adults +/- 5kg (although they are one of the smaller crane species).

- Plain blue-grey in overall colour with very long slate-grey tertials (resembling long tail streamers).

- Long black legs and feet.

- Eyes dark brown.

- Brown to pink bill.

- Forehead and crown very light grey to white.

- Feathers of cheeks and ears are long and loose – are raised during courting displays.

Voice: Distinctive rolling croak, high pitched and loud.

Conservation

Their dependence on open grassland habitats means that the conservation of Blue Cranes relies on the co-operation of landowners. Within the grassland biome, Blue Crane habitat management needs to be included in future plantation planning. Community and Landowner communications programmes need to focus on discouraging the removal of chicks from the wild. A better understanding of overhead powerline collisions is required, which constitutes the most significant threat within the Karoo biome. Throughout the country, but especially in the Overberg / Swartland regions, more responsible use of agri-chemicals needs to be encouraged, especially by the farm staff who bait grain to catch birds for food.

PROTECTED AREAS AND IBA’s

The Steenkampsberg plateau, proposed Grassland Biosphere Reserve, Platberg Karoo Conservancy, KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg Park, Impendle Nature Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal Mistbelt grasslands, Karoo Nature reserve, Overberg wheatbelt and De Hoop Nature Reserve.

Distribution

The Blue Crane is endemic to Southern Africa and is our National Bird, with a very small population in the Etosha Pans (northern Namibia) although there may be a flock in the western part of Swaziland. It has the most restricted global range of any crane species. This restricted range and the bird’s rapid decline over large areas of this range over the last three decades qualifies it as Vulnerable. The loss of grassland breeding and foraging habitat and the poisoning of birds has led to this decline in population size.

While locally abundant in limited parts of its range, it is now rare in most parts. Its population may be divided into three, with one portion of the population extending from Limpopo, through Mpumalanga, the N.E. Free State, and KwaZulu-Natal into the northern parts of the Eastern Cape. A second group occurs in the central Karoo, from the Northern Cape extending into the southern Free State and Eastern Cape. The third group is centred on the south Western Cape (Overberg / Swartland regions), where it is a relatively recent colonizer of agricultural areas. The birds have all but disappeared from the northern areas of the Eastern Cape and occur only as an occasional vagrants in Lesotho and Botswana.

Ecology

Blue Cranes favour short grasslands, and in common with the Demoiselle Crane (A. virgo), are not dependent on wetland habitats for breeding. Within the grasslands, the species is more abundant and evenly distributed in the eastern sour grasslands (where natural grazing of livestock is the predominant land use). In the arid Karoo, the species is found in areas where perennial grasslands are dominant over the more typical scrub Karoo vegetation of the region. In the Western Cape, the species is restricted almost exclusively to intensively cultivated habitats (mainly cereal crops and small livestock farming).

Blue Cranes are summer breeders, nesting from late September through to February. Preferred nesting sites are secluded open grasslands with full view around the nest for predator evasion. A clutch of 2 eggs is laid, generally in a shallow grassy depression or simply on the bare ground. Occasionally, Blue Cranes may nest in shallow seasonal wetlands, particularly where livestock numbers are high and risk of nest trampling is increased. In agricultural areas, they nest in pastures, in fallow fields and in crop fields as stubble becomes available after harvest. The Blue Crane is termed a ‘partial migrant’, gathering in large flocks during the winter months having moved out of their breeding territories. Our understanding of their movement patterns is limited but an assessment is currently in progress, using satellite telemetry and colour ringing. Movements appear to be more localized than previously thought with flocks moving in large groups within their sub-populations (e.g. the sub-population in the Karoo biome) and not mixing throughout the country.

Population

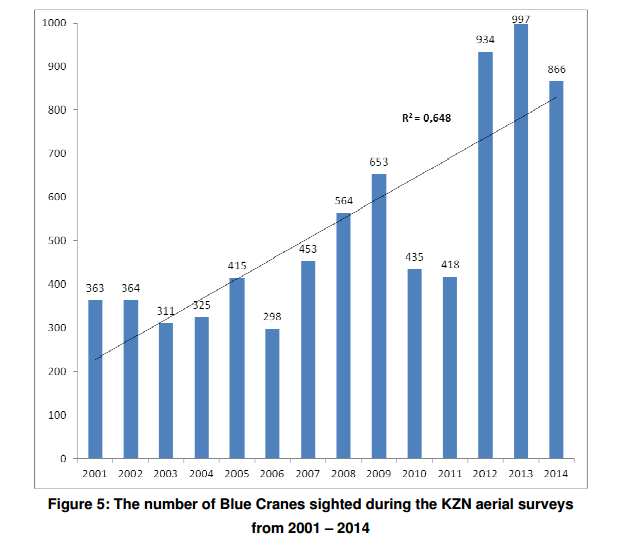

Although this species is still found throughout much of its historic range, it has experienced significant and rapid local declines over the last three decades. The most recent estimate puts the population at 21,000 individuals. A National Crane Census undertaken during 1998 identified 19,919 birds. The majority being found in the Karoo habitats and the agriculturally transformed Renosterveld of the Western Cape. 10,650 were located in the Overberg / Swartland region of the Western Cape (53,5 % of South Africa’s population), with other significant populations in the scrub Karoo of the Eastern Cape (3,300 centred on Graaff Reniet) and the grassy Karoo of the Northern Cape (2,650 centred on De Aar / Hanover). The remaining populations within Mpumalanga, the north eastern parts of the Free State, KwaZulu-Natal and the north Eastern Cape have shown marked declines, and in the areas of Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal, declines of up to 80 % in the period between 1980 and 2000. Since then the population in this region has steadily recovered from under 400 birds to over 900, largely as result of the increased awareness of the plight of cranes by farmers and their co-operation in crane conservation.

The EWT, Ezemvelo KZN crane survey indicates a steadily increasing population of Blue Cranes in the KZN area during the period 2000 – 2014

Threats

A combination of grassland habitat loss through land use alteration and agri-chemical poisoning are the primary causes of the decline in Blue Crane populations. The alteration of large tracts of grasslands to mono-cultures of maize crops and commercial afforestation has limited the suitable open grassland habitats required for successful breeding and foraging. Over 1,3 million hectares have been converted to forestation in South Africa, mainly in the wetter eastern parts, there is a high likelihood that this land use conversion will increase in the future, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape Provinces, as the department of Forestry aims to add 10 000 ha of net new afforestation a year.

The documented decline of Blue Cranes has coincided with many reported cases of poisonings from all parts of the country, although proportionally more have been reported in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces (where large populations of Blue Cranes are found and can be expected to occur in crop fields). Poisoning in the past has been through intentional and deliberate poisoning of cranes causing crop damage, the inadvertent poisoning aimed at killing other species causing crop damage, or accidentally through the normal application of agri-chemicals to croplands. Currently, poisoning cases are as a result of farm workers either directly poisoning cranes, or inadvertently poisoning them when baiting grain for gamebirds, for extra food protein. Another significant threat is the removal of young Blue Crane chicks, prior to fledging, from the wild to be kept as pets, for food, or to sell to bird breeders.

A further significant threat results from collisions with power-lines, and more recently with wind-turbines on wind farms. These hazards pose a constant threat to flying cranes, particularly young birds, as they tend not to scan the the area ahead of themselves when flying. Eskom has recognised the hazard that power-lines pose to all large birds and have worked with conservation bodies in hanging markers on power-lines in known bird corridors, nevertheless it is believed that most bird mortalities caused by power-line collisions go unreported.